Abstract

In our consulting and teaching work we are challenged to meet a pressing requirement to increase the adoption of Systems Thinking to current societal challenges. As students of the pioneering thinkers in management, Beer, Ackoff and Deming we now see the struggles as their holistic emergent thinking is applied narrowly and formulaically.

Using information from occupational preferences we recognise the difficulty of Systems Thinking for the adaptor personality: a profile of tool users, of reductionist thinking and checklist methodologies.

Geoff Elliott & Roger James

Learning Management

It is perhaps a mixed blessing that we are seeing a growing interest in Systems Thinking as organisations in the public and private sectors both require better techniques to cope with pace and complexity of change. But this interest is being met with a mixed response from those providing answers and solutions. Systems Thinking is at the tipping point – where great work can re-establish the important of Systems Thinking in the portfolio of interventions, or where the influx of ill-advised applications led by a coterie of poor consultants guarantees it is seen as a short term fad.

Our point of view comes from working as both practitioners and academics and working for 30 years. Avoiding age related dogmatism – the rigid orthodoxy of approach – we believe we approach assignments as open minded but not empty headed. We have built a perspective across many techniques, grounded in the past and challenged by the future. It spans the classic works of Ackoff, Beer and Deming developed in the factory and manufacturing but now applied to the global, technology led, knowledge industries. It is an era during which the use of information has been revolutionised from the slim pickings used for the elegant theories in Operations Research to the brute force of big data and model-less heuristics.

The practice of Systems Thinking has been adversely affected by the schism that appeared in Operations Research: in the early 1980’s the discipline split. The chasm was between the methods for simple problems deemed incapable of dealing with complex social problems, and the methods for complex social problems too academic and obtuse for every day needs. The pragmatic middle, delivering practical solutions for difficult problems, became a barren area for academic research yet a significant area of our real world assignments and practice.

Boisot and McKelvey have developed their own critique of the difficulty of organisational science – Management scholars thus face a stark choice: (a) either say something that practitioners want to hear but do so through narratives in which rhetorically dramatic effects are achieved at the expense of academic rigor or (b) maintain academic integrity by sacrificing perceived practitioner relevance. They are trapped between the characteristics of idea propagation which demand wide applicability and the need for idea novelty which demands academic purity. In Systems Thinking this is a specifically acute problem – real world problems, the wicked problems of Rittell and Webber.., often produce hybrid even mongrel solutions. The pure meme-otype, beloved of academic research, is seldom encountered in practice despite its prevalence in case studies. Real solutions and the real world often involves fuzzy boundaries, purposeful agents and things that cheat.

Current practice in ST appears caught between the over-simple and over-elaborate. In the former critical elements and behaviours of the systems are ignored and simple solutions are forcibly applied, in the latter the complexity and detail of the technique appears out of line with a practical parsimonious solution. Either way ST stands to fail.

There is great variety in Systems Thinking Approach or as they are called methodologies. It is easy to know how to use each approach but the struggle comes with knowing why to use a technique or when to use it. Alternatively, we invent specific approaches, the latest being lean systems thinking, in ignorance of what has gone before in the belief of the new universal answer [the curse of the management fad].

Principled Cheating

Anyone familiar with Ackoff’s work will recall his example of the mirror in the lift as a way of ‘solving’ the engineering of the slow lift – the shortest version of this comes from Re-designing Society and simply states “Complaints of occupants of an office building about slow elevator service were dissolved not by speeding up or adding elevators but by putting mirrors on the walls of the waiting areas. This occupied those waiting in looking at each other or themselves without appearing to do so. Then time passed quickly“. Much longer, more elaborate and suitably embroidered versions of this story appear in his other books – amplified to meet the sense of drama and pathos required of the academic writer.

In a practical engineering sense the mirror solution is no solution at all, but in the complex, real social system it is a clever and dramatic intervention. We teach the rock and bird metaphor: imagine trying to throw either into a waste paper basket at the far end of the room. Both obey the laws of physics – such that ballistics, gravity and aerodynamics are applicable to the trajectory of either. For the rock we could write a case study of formulating the problem, of solving the range of differential equations and of the training required of the thrower – all finishing with the event where the Olympic standard athlete hits the target: a perfect solution for an unreal and restrictive problem. Contrast this with the bird: here to achieve the objective the best solution cunning replaces athleticism. Simply place bird food in the wastepaper bin and without the need for the big equations, or the hero athlete we produce a much more applicable, scalable and robust solution.

People Cheating

Guilfoyle from the perspective of a serving police officer presents an excellent critique of the manic marriage of targets and deliverology so characteristic of the recent government agenda. The strength of the critique makes the case for authentic systems thinking but sadly here no answers are provided.

At the core of the criticism of the theory of governance by targets lies two overriding flaws with the reliance upon:

- ‘Synecdoche’—taking a part to represent the whole. In performance terms, this is where one takes the performance of a part of the system and interprets it as a surrogate measure of the whole system’s performance;

and

- The assumption that governance by targets can ever be immune to ‘gaming’.

[It is ironic that the biggest critics of deliverology fall into the trap of synecdoche in their own critique in denouncing all targets un-categorically, without understanding the difference between good targets and bad targets. The challenge lies in discriminating between good and bad, not in decrying targets].

These criticisms are addressed by the appropriate use of Systems Thinking approaches: they are based on holism and address purposefulness.

Sharp Tools: Blunt minds

The pioneers of Systems Thinking ranging from Beer to Boulding or Deming would not fall into this trap; they understood the characteristics of the human world and the complexities that lie within. They had time to think – from the period where there were few one-size-fits-all solutions and where an elegance of ideas had to compensate for a shortage of data.

Socrates in his teaching had a strong distrust to writing suggesting that “it will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory”. Whilst Boulding encouraged the use of techniques he was equally guarded:-

“By means of mathematics we purchase a great ease of manipulation at the cost of a certain loss of complexity of content. If we forget this costs, and it is easy for it to fall to the back of our minds, then the very ease with which we manipulate symbols may be our undoing. All I am saying is that mathematics in any of its applied fields is a wonderful servant but a very bad master: it is so good a servant that there is a tendency for it to become an unjust steward and usurp the master’s place”

It is simple human nature to apply what we know, in contrast to what is needed. This is evident in the current fixation on lean methods as the one solution to improving efficiency; without asking questions of effectiveness. we need to understand where, when and if this is an appropriate response. Many excellent ST approaches are featured in the academic literature; such as Systems Dynamics, Senge’s organisational learning school or the interest in wicked messy problems.

Systems Thinking Approaches or Approaches to Systems Thinking?

So what are we to do – our common challenge is how to teach Systems Thinking and Systems Practice usually in a practice setting but also academically. Typically our audience comprises ‘middle experience’ staff usually with a background in lean and Six Sigma. Usually we struggle with the gap between the strong analytical traits often well developed in such groups and the conceptual understanding needed for Systems Thinking. In this respect many people do not understand the difference between analysis and synthesis or to put it another way, convergent and divergent thinking.

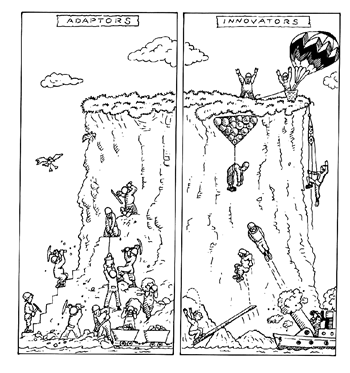

In response to a request from one such group for a checklist of Systems Thinking we realised the central problem, it was the problem epitomised in the following cartoon [taken from the Open University course on creativity). Based on occupational profiling studies by McBer reported in Competence at Work suggests 5% or less of individuals are naturally conceptual thinkers [the innovators of the cartoon].

In our consulting the difference is obvious and immediate, a few individuals are instinctive Systems Thinkers the majority, adaptors, are the ones who need a checklist for Systems Thinking whose focus are the steps and stages of the approach rather than the concepts and the problem. Individuals looking to Systems Thinking as the next step from a procedural discipline such as Lean or Six Sigma become trapped in the detail without appreciating the conceptual basis.

A step-by-step Systems Thinking approach for Adaptors

Russell Ackoff in his work had the opportunity for the grand gestures and sweeping critiques – excellent in conference but poor as an instructional technique. Looking for a checklist approach adapted for adapters we began with the series of articles on Systems Thinking by William Dettmer. In Part 6, entitled Systems and Constraints: The Concept of Leverage, Dettmer introduces the Theory of Constraints reminding us of the importance of the system constraint as the only point of useful intervention.

This is the complete antithesis of the typical wicked problem but, usefully, it represents one end of a spectrum of systems intervention – the end represented by a closed system, defined by analysis and requiring the optimisation of a single variable. As we study any systems – under conditions of change, longer timescales, the introduction of social factors – we can start to identify where the models weaken and approximations become invalid. This is the practical illustration of George Box’s dictum “all models are wrong some models are useful“, our practical world is comprised of a number of simplifying assumptions which allow us to be efficient but which, unless challenged, ultimately cause us to be ineffective.

Systems Thinker often criticise reductionism, breaking a system into smaller and smaller parts, but as explained by Anderson the real challenge is to understand constructionism – how to move our students from the narrowing reductionist approach to the correct constructionist thinking. Anderson in More is Different makes the fundamental point that reductionism and constructionism are asymmetric, you can always dissemble a system by reductionism but there is never a guarantee that you can re-assemble the parts to the original, or to a coherent, whole.

We may borrow the funnel experiment from Deming to explain the operational difference between reductionism and constructionism. Whilst pouring liquid into a funnel the flow is aligned and narrowed to a finer and finer focus: reductionism works! Reverse the simple linear flow from the narrow spout and the output is complex, the direction is unpredictable and the asymmetry is evident: constructionism is problematic!

This brings us to one of our techniques that help bridge the gap … the new factors prism.

Figure 1 The spectrum of problem solving approaches applicable to the closed physical systems on the left ‘the world of manufacturing’ to the open often social systems on the right ‘the world of purposeful systems’

On the left we have the approaches for closed systems within limited problem dimensionality, often requiring optimisation. As we move right, driven by conditions of change or open systems, the difficulty of resolving the situation is made more difficult as the number of dimensions increases. As the situation becomes more complex and the problem becomes more wicked we require a systems thinking approach, such as VSM, SSM, CSH and so on. The challenge is to first recognise that the situation being studied is no longer a closed system and then to identify which, of many possible, Systems Thinking approaches will provide insight.

The challenge, introduced in the section on tools, is that the danger is that we force the approach before we understand the problem and here we offer our prism technique to use the problem characteristics to guide us towards an appropriate approach. It uses reductionist techniques to identify constructionist approach and bridges the adaptors world of analysis to the innovators world of synthesis.